Editor’s note: Public media relies on its users — its listeners, its viewers, its readers — for much of its support. But as the disruption of media continues apace, there are some who are concerned those patterns of support may not carry over as users’ habits shift.

Melody Kramer has spent several weeks here at the Nieman Foundation as a Knight Visiting Nieman Fellow, examining a set of questions around that issue. How can the bedrock concept of public media support — “membership” — be broadened and strengthened? How can people contribute to their local stations through something other than money? And how can public radio and television become more ingrained, more essential, to the communities they serve?

I’m pleased to share her report with you — I hope it’ll be read widely both inside and outside public media. If you’re interested in what she’s launching out of her research, Media Public, sign up here.

Last summer, public media consultant Mark Fuerst interviewed 40 front-line development professionals at public media stations. Fuerst noted that the people he interviewed expressed concerns about the continued effectiveness of their ability to raise money over time. Two-thirds of the membership directors at radio-only licensees reported that both incoming pledge drive calls and online pledge had declined. Six of the 15 radio-only licensees reported a decline of over 10 percent.1

These trends, coupled with continuing changes in patterns in public radio consumption,2 demand new approaches to thinking about the sustainability of the current membership model. Individuals supplied 34% of funding to member stations in 2013, and the importance of pledge revenue to stations’ bottom lines, as Fuerst notes, is “impossible to overstate.” As modes of listening shift, however, it will become increasingly difficult to cultivate donors using the traditional methods of fundraising.

What, then, is the alternative? How can we encourage people to become invested in the future of public media, both as listeners and as members? In this report, I describe the results of a multi-method effort to detail an alternative membership model for public media stations. This model is based not on the pledge drive (or on cultivating sustaining donors or large donors,3 as many stations seek to do), but on building an infrastructure that allows community members to contribute to their stations in a variety of ways, including non-financial means.4 It takes as its starting point the understanding that building relationships with potential donors leads to their sustained support — in the form of time, money, and advocacy on behalf of the station.

Why do we need a new membership model?

What could a new membership model look like?

There are a number of ways in which community members could contribute to their local stations — thereby building connections with both contributors and potential donors.

At the end of the first year of non-financial membership, these contributors could be asked how they would like to renew their membership: By volunteering additional time, recruiting additional volunteers, and/or donating financially.

What are the challenges to implementation?

How can these challenges be addressed? What are the next steps?

The remainder of the report is organized as follows. First, I detail how public radio stations currently offer membership. Then, I detail the ways in which stations could strengthen their relationship with their communities by asking them for non-financial support — and look at the way several other organizations approach membership, engagement, and sustainability, and what public media can learn from them. Lastly, I detail key takeaways and recommend next steps.

Public broadcasting is part of the fabric of our civic democracy. It helps inform and educate the public, and it does so without being beholden to advertising dollars. If we want public media to continue to be able to play this role, then we need to think about new and invigorating ways of defining membership and redefining the public’s relationship with public media.9

The concepts of membership and loyalty have a long history in the fields of social psychology and organizational behavior. In general, this research shows that people who identify with an organization describe themselves to others in terms of that organization. For example, people who identify with public media are likely to describe themselves as NPR listeners on social networks and on dating websites.10 And when people identify with an organization, they exhibit higher and longer-term levels of loyalty and are more likely to formalize their identification by becoming members through donations.

Though membership11 has always been a core part of public media, public radio12 has been grappling with new questions concerning membership and listener loyalty over the past several years. The traditional form of building membership and leveraging organizational loyalty — the pledge drive — has declined in effectiveness, and new conversations are beginning about how to recruit and retain members who access content off-air.

The existing membership model for public radio is largely based on a single assumption: that people who want to listen to the kind of high-quality programming that public radio provides will eventually find and then listen to public radio — on the radio, in the car, or on a mobile device. But the assumption that public radio provides a particular type of listening experience may no longer be accurate. As Kevin Roose noted last October, 50 percent of all cars sold in 2015 are connected to the Internet, and 100 percent of cars will be connected by 2025. Though many stations have developed mobile apps, and NPR has developed mobile apps and continues to create experiences for connected cars, several for-profit podcasts and podcast networks — like Gimlet, 538, Midroll, BuzzFeed, and Slate13 — now sound virtually indistinguishable from the NPR aesthetic,14 and will grow alongside other podcasts15 as they become easier to access in the car, which remains the primary listening place for audio. (Forty-four percent of all audio listening now takes place there.)

The rise of connected cars will also require new techniques to engage current millennials16 and Generation Y-ers, who are not likely to age into the same listening,17 commuting,18 or donation habits as previous generations. Millennials are more likely than baby boomers to give small amounts of money to a lot of organizations,19 and may be more likely to invest in a one-off Kickstarter campaign that makes them feel like part of a larger community or cohort than to become a reoccurring donor or sustaining member.20) Like their parents, however, they’re more likely to support or invest in an organization if they feel some connection to the organization, its mission, or the benefits of becoming a member.

These trends demand new ways of thinking about public media membership and about the kinds of relationships people have with their public radio stations.21 More active donor relationships, which lead to greater donor loyalty, can be cultivated through building trust with people, increasing the number of two-way interactions with potential donors, and by teaching people the importance of the organization itself.22

These interactions don’t always have to start with acquiring financial donations. In this playbook, I articulate how stations can cultivate other kinds of relationships with the public that will lead to stronger and more loyal advocates for public media.23 A failure in the coming years to push outside the existing envelope of membership will leave audience growth stalled, potential support diverted, and significant amounts of funding on the table.

There are several different ways the public can currently donate to a member station.24 Most of these are financially-based donations. The WNYC website lists nine different donation methods for the public, including donating money, participating in an employee matching program, donating a vehicle, creating legacy gifts, donating stocks, and purchasing tickets to events.

Some public radio station websites make it difficult for people who would like to give a one-time only gift. “They’re less welcoming to the $25/50 donors,” a veteran public radio membership consultant told me. “There’s been a major shift towards sustainable donors.”

Sustainable donors pledge annual donations to a station. They have changed the dynamics of stations’ annual pledge drives. Fewer people are calling into the pledge drives because sustaining donors have already agreed to be automatically renewed indefinitely. (Upgrading sustainers to higher annual levels and/or additional gifts are also key parts of current sustainer best practices.)

Other key innovations related to financial support include the following:

Nine interviews were conducted with membership leads between May 8, 2015 and May 29, 2015. Other station information was found on station websites.

Most stations in the top 100 markets give members some of the following benefits for contributing financially:

Donors who contribute at higher levels often receive:

A few stations also offer some unique perks for members:26

Many stations run robust volunteer programs, but the ways in which people can contribute are limited. Most often, these volunteers help the station by:

Two stations of the nine interviewed grant membership perks to volunteers, though this information is not mentioned on their membership pages. One station grants membership for a year to qualified volunteers; the other gives a member card, but not membership, to volunteers who contribute 50 hours.

Louisville Public Media (LPM) is an independent, community-supported nonprofit corporation that comprises three public radio stations: 89.3 WFPL News, Classical 90.5 WUOL, and 91.9 WFPK. The stations receive no city or state support. Ninety-three percent of their funding comes from the local community, including 42% from membership.

The stations have more than 200,000 weekly listeners and a robust volunteer program. During their pledge drives, more than 500 volunteers come to the station to help. Another 327 volunteers help out year-round and are emailed once or twice a month with ways to help the station. Thirty-four percent of all of LPM’s current volunteers are also financial donors. Of the active year-round volunteers, 60% are active members, 20% are lapsed donors, and 20% have never donated financially — despite actively volunteering.

Membership manager Kelly Wilkinson is participating in Media Public’s pilot program and plans to make the active volunteers who have not donated financially full-fledged members of LPM for the next year.

“They’ll receive a free monthly magazine subscription to the Louisville Magazine and a free lunch anytime they want to come to one of our free lunchtime concerts, and they’ll get all of the perks that we email our members every week,” says Kelly.

After eight months, the volunteers will receive communication asking them how they would like to renew their membership: with a financial contribution or with another set of volunteer hours.

And what could volunteers do? Kelly imagines a lot. “We have a storage room here full of magnetic reel-to-reel tapes that we’d love to convert,” he says.

Kelly also tells me about a Summer Listening Program that Classical 90.5 WUOL runs for young people.

“It’s like a summer reading club,” he says. “There’s a couple of hundred kids who participate. They receive a list of classical songs that they have to listen to, and our program director puts out information about each song, along with emails and videos.”

This year, Kelly is thinking about making the kids who participate in the listening program members as well. The idea to make young people members is similar to something National Park Service has implemented for next year. They have started a program to give all 4th graders in the United States a year-long park pass to the National Parks.

The White House says the idea is to get kids into safe outdoor spaces, and to make it easier for children to be outside instead of in front of screens. I suspect it also has some substantial additional benefits. Many of those fourth graders — not to mention younger and older siblings, parents, cousins, grandparents, friends, etc. — will eventually:

Kelly says he is interested in tracking whether the young listeners who receive a similar benefit from his station will grow up to identify as supporters of public radio. This is an experiment well worth testing in other markets as well.

Currently, station volunteers contribute most of their time and efforts to the membership and/or events departments at a station.27 Fewer opportunities exist for people to contribute within the newsroom or in programming.28

WYSO in Yellow Springs, OH is one notable exception. The station has ongoing volunteer opportunities for those with experience in journalism, research, editing, oral histories, and photography. The station also runs a program called Community Voices, which trains local people in recording and editing commentaries for use on their airwaves.

Neenah Ellis, WYSO’s general manager, also tells me about an additional program the station runs for young professionals. Called NextUp, the program brings together young people in the Dayton area to volunteer at events in the area.

“They set up a table and act as a presence for us,” says Ellis. “And it’s great because they’re able to meet each other and think ‘WYSO’s cool and brought us together.'”

Many of the stations I analyzed do not currently offer ways for volunteers to contribute professional skills to their local stations. As a result, stations are missing opportunities to engage people who have little interest in traditional volunteer activities (e.g., clerical work, pledge drives) but who are motivated by opportunities to contribute and develop professional skills,29 meet and network with other professionals in their communities, and contribute to projects they deem meaningful or important.30

There are fears across the system that having volunteers complete tasks will take away work from existing or future employees. The tasks I outline throughout this report are not designed to compete against professional roles at a station, but rather to help strengthen the whole system as well as a station’s ability to focus on more specialized tasks and complete and/or strengthen existing work.

There are many different ways stations could benefit from professional volunteers. Here are example activities that could help both a station and a person contributing non-financially. Contributors could:

If these events are held in person, community members could meet one another, develop new professional skills, learn more about the station and ways to get involved, and help out with projects that would help strengthen the station as a vital local resource.31 In return, volunteers can enhance their own skills, meet people in person, and strengthen their local community.

We can also look outside of public media to see how other organizations engage professionals:

What happens when stations bring community members into the process in these ways?

The Park Slope Food Co-op is the largest food co-op in the country. Members at the Park Slope Food Co-op pay a nominal fee to join and then work 2.75 hours a month to maintain their membership.

“In the orientation34 that you take when you become a member, you learn all sorts of wonderful facts, like the fact that they turn over more produce than any other grocery store in the country,” says member Jeremy Zilar.

Jeremy, who has been a member of the co-op since 2003, is a member of the team redesigning the Co-op’s website. Members of the website redesign team are working hand-in-hand with members of the co-op staff, to make sure their website’s needs are met. In doing so, the website redesign team is also introducing the co-op staff — and co-op members — to new online tools and new ways of thinking about technology.

“I wanted to see if it was possible to make this a very open design process,” says Jeremy. “How do we utilize as many members as we can in this process?”

After putting out a call for help, Jeremy found developers, designers, photographers, user research professionals, filmmakers, and product managers who wanted to help with the co-op’s website. Additional members wanted to provide feedback and support, so the team of developers created a website where everyone could register their input.

“Most corporations that make websites, they do it by having 4-5 people go off in a room and make something that everybody has to live with,” he says. “We didn’t want to do that.”

The Co-op’s redesign is designed just like the organization itself: infused with the spirit of cooperation. And as a result of being included in the process, members are really excited to see the final results.

“By including them in the process, they feel involved,” says Jeremy. “Everyone is contributing, and everyone is invested in the outcome. It really raises the level on all fronts.”

This is very smart. Instead of hiring an outside development team, the co-op relied on members, many of whom had skills to redesign and create a website. In order to make an effective project for the web development team members, the co-op decided to:

The people involved in the project also have benefited and associate their benefits with the food coop itself. They’ve made valuable networking contacts with people who work locally but at other organizations, and contributed to the co-op in a meaningful way that takes advantage of their skillset.

Stations that are affiliated with a university rarely, if ever, collaborate with the computer science, library, and design schools that are also affiliated with the university. Often, students in these departments have to participate in a capstone seminar or complete a thesis. They are unaware of ways in which they could help their station or volunteer in ways other than stuffing envelopes or answering calls during pledge drives.

Stations can and should form partnerships with local universities, many of which have startup competitions as well as students who would like to strengthen their own design and coding portfolios before graduation.

Creating meaningful partnerships at university-affiliated stations can introduce students to public media stations and help them obtain skills or portfolio items that they can use to obtain jobs after graduation. Other organizations already do this well with events: orchestras offer free tickets, downtown museums offer free or discounted tickets to students, and other arts groups engage students through events and activities.

Public radio stations have the opportunity to introduce students to more than just events. Here are examples of activities, categorized from high levels of effort to low levels of effort, that stations could do to engage students on university-affiliated campuses:

If students or staff participate in any of these opportunities, stations can sign them up for an e-newsletter, let them know about future events, and reward them with year-long memberships.

In Spring 2014, graduate students at Carnegie Mellon University taking Ari Lightman’s Measuring Social class worked with two members of NPR’s Social Media Desk to define a ladder of engagement for people who had encountered NPR content online.

The students spent their semester identifying the behavior and demographics of the people who encountered NPR’s content online, then mapped NPR’s goals to each level, and finally identified how NPR could monitor progress and make potential users of their digital community more active.

The students participated in biweekly conference calls with NPR’s Social Desk. (Full disclosure: This was my team and I was one of the two people.) The students did extensive research and created an engagement strategy that helped us think about new ways to create digital experiences for our audience.

NPR benefited from both the research and fresh eyes the students brought to the project. The students benefited too: they got to use the work in their portfolio, I offered to write them letters of recommendation for future jobs, they received course credit, and two of them told me that they were interested in pursuing careers in public media because of their work on the project.

Not everyone has the ability to help a station in person. Only relying on community members who can travel to a station for support is limiting: not everyone has the time or capacity to travel to a station. People in lower income brackets are less likely to have the time to “work” in exchange for “membership” and limiting membership to those who can donate money or donate time in person is not inclusive, and limits the type of people who receive membership benefits.38

We can think of ways that people can contribute to a station remotely and accrue the benefits of membership. Examples of remote professional skills that could benefit a station could include:

Other institutions have worked with remote volunteers and have set up software platforms to assist with these efforts. Most help to add metadata to content. Metadata is important because it can help resurface archival material in different ways, or help categorize content in new ways.39

The projects save the institutions time and money, and deepen their relationships with those who invest their own time in these efforts. They are also designed so that multiple people have to add the same data, and multiple people who add that data have to agree on the data type. This eliminates concern that the public may add incorrect data to a project. Some examples:

Other projects exist that reward contributors with benefits:

The Smithsonian Transcription Center started in June 2013, when 1,000 volunteers transcribed 13,000 documents. To avoid errors, multiple volunteers work on each page, and a Smithsonian employee reviews each document for errors.

Two years later, volunteers have fully transcribed and reviewed over 100,000 pages43 and generated greater interest within the Smithsonian to digitize even more of their archive44 — and doubled the in-person volunteer corps.

The effort has been a major success, in part because of the efforts of project coordinator Meghan Ferriter, who has helped create a community amongst the remote volunteers who transcribe material.45

And volunteers really enjoy working with Meghan in return.

“The most common feedback I hear is “thank you for this opportunity” — [and] we are grateful to the volunteers!!” she says. “Yet, they are thrilled to be given this chance — to be TRUSTED to participate meaningfully by an authoritative institution. I think volunteers are slowly (and rapidly for this institution) changing the culture and thinking around engagement, sharing collections more openly, and what the future of the Smithsonian will be,” she says.

As they work, volunteers often realize they have a deeper connection with the Smithsonian. For example, they tell Smithsonian employees about their personal experiences visiting the museum or benefiting from a previous encounter with a Smithsonian collection or staff member.

The average length of time that volunteer contributors spend on the site is 27 minutes and 27 seconds. In return, volunteers are often the first to see newly digitized collections and have immediate access to the work they create in the form of a PDF, says Meghan. When the entire project is completed by volunteers, it too is made available — both to volunteers and the public.

“Volunteers also have been given behind-the-scenes access via Google Hangouts and livetweeting to curators’, catalogers, and even the Secretary!” says Meghan. “These are not regularly scheduled events, but rather have emerged as a result of engagement with and completion of projects. It also allows volunteers to ask staff direct question, learn more about the work of staff, and see the less-frequently seen physical space of the Smithsonian.”

Initially, there were some fears at the Smithsonian about whether the public could transcribe and catalog accurately, and whether volunteers would be taking on tasks that could be completed by staff members. Those fears have been dampened over time, says Meghan, because she constantly sets expectations and shares success stories, and the volunteers’ work allows employees to focus on more specialized tasks. After every digitization, she says, her coworkers respond enthusiastically about doing it again.

Now, she is thinking about other ways to work with remote participants.

“I would love to see volunteers take their “product” or their process and apply it to other Smithsonian projects,” she says. “For example, transcribed an address book? Great, now please map the coordinates of the addresses. We have actually seen small examples of volunteers taking Smithsonian data forward to other spaces: connecting details, completed projects and finding aids to Wikipedia, entering observations from ornithologists and birders as historical observations on eBird (this one is a HUGE deal!), and connect what they’ve learned about scientists and artists to other CitSci/digital humanities projects.”

“I would like to see image parsing, image identification, decision trees, metadata elaboration (via tagging, etc), audio transcription, translation (a tricky one!), personal story “donation” and more,” she continues. ” And I would like volunteers to be able to donate their time/skill in other ways, especially donating time to refine our site and products via development or coding. I think creating a collaborative space for creating better experiences and a “wish list” of delights would be amazing; there are many ways we could share and build a more useful future with the public.”

Developers and designers who would like to contribute development support or code can help stations create online reporting experiences that stations would otherwise be unable to create. They could also adapt already-existing projects for their own use, which could spur all sorts of new innovation within public media,46 and show the impact of creating such technologies to potential funders.

WNYC is the only station that lists the ability to donate code47 on their website, though they don’t yet extend membership to those who have donated their coding talents. There are also a few stations that occasionally work with outside developers who would like to contribute code to a station. For example, several stations have worked with community organizations to create one-off coding projects, though they haven’t yet extended membership to those who donate in this way:

There is no platform that exists for stations to articulate how members of the public could help with existing coding projects.48 If such a platform existed, members of the public could help existing public media developers49 with projects, or help suggest new ones. Stations would also be able to articulate what problems they might like to solve — either individually or collectively.50 Stations would also be able to more easily collaborate with each other.

Many stations do not have GitHub accounts and those that do, don’t often make their code repositories public.51 Developer Andrew Hyder, who works at Code for America, recently adapted their issue finder to create a way for stations to show any open source projects they have and how the public could help. For example:

Partnering with local software companies on small, focused projects on a quarterly basis could increase their donations to the station or their employees’ affinity for the station. The partnership with a public radio station also benefits the company: they can then talk about their pro bono work, learn about new pain points that could possibly be solved through software, and work on meaningful work with immediate benefits in the community they live in.

For this to work, stations would need to clearly articulate their needs and the ways in which developers or designers could help. One good and easy way to do this initially would be to release a batch of archival material, and ask for a firm’s help in sorting, categorizing, surfacing, or displaying the material. This does not require a heavy lift on the station’s side and would have immediate results that could be accomplished in a limited period of time.

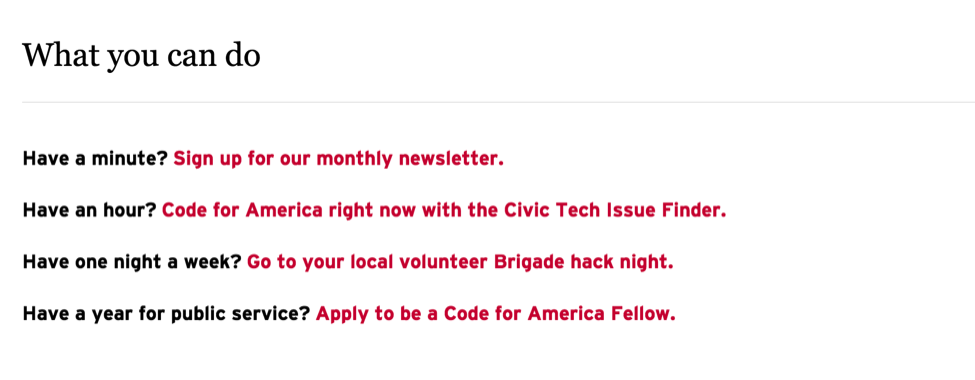

Code for America is a nonprofit organization that pairs technologists with local city governments. The cities pay less than market rate to receive a pair of technologists for the year. The technologists then work with the cities and city officials to build websites and software that make government services easier to access.

The model is one that public media could look at for ideas for how to engage community and make the community more invested in the future of public media. The technologists working with Code for America become more invested in the future of the cities themselves — and often get involved more deeply or in other ways.

Projects that Code for America has launched or incubated include Promptly, which helps inform citizens about city services through text messages, a public art finder, a platform for city residents to quickly apply for business permits, and a way for citizens to claim a fire hydrant to shovel out after heavy snowfall. The fellows have worked in 38 cities so far.

Why are cities so eager to participate?

“They’re receiving a programmer or a designer for much less than they would pay outright,” explains Jack Madans, who has been at Code for America since its earliest days. “Instead of approaching cities with a free model, we offered to bring in highly talented tech work at far under the market rate. This hacks the value for the city, but the city still has to commit money, which means they’re invested in the outcome. The value of the program is less about the rate of development time — and more about building a custom solution to an urban problem from the ground up in their particular city.”

The program has both a year-long fellowship, which pairs technologists with cities to work on specific open source software projects, as well as a nationwide series of meetups, which they call brigades, where people who care about cities work on coding or civic projects that make the city services more accessible. Code for America’s fellows are paid; members of each brigade are not. Both fellows and brigade members interact at a yearly event called the Code for America summit. The Summit is an annual event that ends the fellowship for the technologists, and they present what they’ve made in conjunction with their city partners, in front of representatives from many cities and civic groups from across the country.

“Everyone at the Summit knows that you’ve spent money and time on this,” says Jack. “No one wants to be the person on stage with their hands in their pockets that says, ‘We didn’t accomplish anything.’ When the [technologists and city representatives are] up on stage, they’re not just talking about their own city’s projects — it’s a spotlight for work that can be taken to other cities.”

With Code for America, cities routinely share code and projects with each other so that they’re not trying to solve the same problems. The program specifically looks to connect city employees across the country who are not yet at the managerial level.

“We want to connect with the people who are not necessarily the ones attending conferences,” says Jack. “They’re people who deeply care about working in cities and have a huge potential for innovation and energy.”

Between events, the group uses Twitter to communicate ideas. Jack says they don’t want their work to be hidden behind Facebook groups, which people have difficulty finding.

“We want people to have conversations with each other on Twitter and follow each other on Twitter — and use Twitter to talk publicly about what they’re working on,” says Jack. “We want it to be open. Twitter is an incredibly powerful way to spread ideas and things that have happened. We don’t want it locked away where no one can find it.”

Where to begin

Code for America stresses to cities that they can involve technologists in their work, even if they don’t have fellows. The group advocates that cities can start by simply making their data public so that coders can begin to work on making websites with it at hackathons.

“Though hackathons are not sustainable, and not meant to replace end-to-end service like the fellowship, they showed cities that they could throw something together in a weekend and show what happens when governments start making their data open,” says Jack. “And then cool things were being written up in the newspaper and cool things about the data were being tweeted, and the governments could see immediately that this was a way to get good positive attention, and bring good people who wanted to contribute into the room.”

Initially, says Jack, the projects didn’t have to be complex. “We could have people put data on a map and make it visual. That’s helpful, and it’s a quick win. Quick wins help establish trust and build the framework for longer-term wins.”

Parallels can be drawn between the way Code for America’s work with cities and the work technologists could do if they were better connected to public radio stations. In both instances, technologists can meet other people like themselves, and work on meaningful problems that benefit the community.

“At our meetings, there’s a sense of camaraderie because this kind of problem solving is hugely attractive to technically-minded people,” says Jack. “They want to work on stuff that matters. A lot of people who are really, really smart are spending their days trying to get people to like, click on ad space. They’re doing trivial tasks at their jobs, and they’re cogs in giant tech machines. We give them the opportunity to work on things that matter and public problems that matter. “

And people like coming together in public spaces — like libraries or town halls — to work on these problems.

“It’s a space for geeks who are not extroverted, who may not like conferences or networking events to find each other, and they get to work on things that matter that they might not be able to get to in their day jobs. And they get to show off their tech skills. There’s a “wow” factor of what they can do.”

There are many public radio stations that could benefit from this type of relationship. The stations could present a wish list of technical help for reporting projects or for membership projects, and ask the community to help. In doing so, the station would help connect people with each other — who would attribute their connections with the station. This would strengthen the station’s relationship with a community.

There is already one station working towards this goal. Last year the Code for America brigade in DC worked with WAMU to create their election night map.52 It was a project the station couldn’t create on their own, so they enlisted community members for help. When I talked to brigade members who worked on the website, they mentioned how much they enjoyed meeting people at the station and working with them on the process.

One last thing: Code for America also makes it clear that they welcome help from all people, even if those people have limited time. This is from their website, which details how people can help in different ways.

Public radio stations and the networks routinely ask their audiences to contribute story ideas, respond to crowdsourcing callouts for upcoming guests, and pass along stories on social media. This is smart because it expands the voices that appear on air53 and expands the stories stations tell.

Asking the audience to enter the storytelling process before the story reaches the airwaves is also smart because it makes them more invested in the outcome, builds trust and loyalty, and creates a community around the piece itself. There are many examples of stations doing this well:

These small asks make community members feel more invested in the outcome of the piece. But community members who give to the station in this way are not treated in the same way as someone who makes a financial donation to the station. While donors receive thank you notes and updates on the station and events, people who contribute story ideas or respond to a call-out are not thanked or even updated on when the piece will air. This may be their first encounter with a station, and it’s a really good one. Stations can and should incentivize them to continue contributing, tell other people about their contributions, and/or give to the station in other ways.

Stations could:

It is important to value the contributions community members make by sharing story ideas and potential sources. Creating easier pathways for them to do so will benefit the stories stations and the networks tell, and make people more invested in their local news.

Several people at member stations told me that they would have trouble engaging the communities in the ways listed above, based on current resources.54 Even larger stations have said they don’t have the capacity to engage potential members in this way. “It’s time-consuming,” said one member station volunteer coordinator. So how could stations begin to find people who might be interested in volunteering a professional skill, time, or code55 — and not create a burdensome process?

There are several software platforms that already exist that could help stations find and then engage potential members56 in this way. I am currently working with several developers to adapt an open-source platform called Midas, which calls itself a “Kickstarter for people’s time.” Midas was originally developed by the federal government and allows any federal agency to post opportunities that federal employees can help with outside of their assigned tasks.

We plan to adapt the platform to allow stations or reporters to post tasks that they would like help with, and would easily allow the public to sign up to help with those tasks. Stations could also articulate whether membership benefits could be given to people who complete certain tasks well. The program will also help stations collect contact information from people who might be able to donate five minutes of time — but not necessarily $100.

Tasks can be completely either remotely or in person, so a reporter could ask for help with an assignment, and a station could ask members to add metadata to stories online.

An alternative arrangement would be to identify and create partnerships with existing local organizations, and extend membership to people who contribute to any collaborative projects developed. Organizations could include local chapters of the civic technology organization Code for America, local journalism coders Hacks/Hackers chapters, and professional MeetUp groups.

This type of professional volunteering may translate into financial donations,57 but it also has additional benefits for both the station and participants:

All of these projects mentioned above also:

We must create opportunities for people to become ambassadors for a station.

Each year, the Vermont State Parks’ Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation runs a state-wide scavenger hunt that rewards people who complete tasks like going for a bike ride, photographing and identifying three types of rocks, and sleeping under the stars.

Jessamyn West, a Vermont-based librarian who told me about the project, says participants are required to submit photos of the activities they complete to the Parks Department, and receive a free state park entry for the following year.

“The state department gets copies of all of your photos so they can see how people are using the parks,” she says. “And what do you get? The ability to play again.”

People love the program, she says, and are likely to put the photos on social media — which lets more people know about the program.

“Parents have a thing to do with their kids that’s interesting, and it incentivizes people to come visit different parks around the state,” she says. “Unless you look at the program as lost revenue — which is negligible — it’s kind of a win-win.”

Imagine a similar scavenger hunt framed around public media. Tasks could include:

Photos could be sent to a station and exchanged for a one-year membership or for a discount on an event. The station would be strengthening community while getting feedback from community members on what resonated with them the most. In addition, the program could create opportunities for cross-generational participation. Imagine grandparents working with their grandchildren on a public radio project — and introducing them to a station in the process.

We must create ways for people to explore the physical space of a public media station.

Jessamyn West pointed me to a passport program run by the Vermont Library Association. The VLA handed out passports to be stamped at public and academic libraries. The passport program was designed to introduce people to different resources around the state. Participants were encouraged to share their “library adventures” on Facebook which, in turn, introduced more people to the library.

Jessamyn says the initial cost of the program was about $100 — $50 for printing the passports and $50 for printing the stamps.

“It encourages people to visit the library,” she says.

Imagine a similar program in a local community, where one of the passport stops was visiting the public media station. This would get people from the community into the radio station, where they could share story ideas, see how the station operates, and learn about ways to become more deeply involved.

In Jessamyn’s town, she says the library is a center for the entire community.

“The library manages to be multiple things for multiple people,” she says. “People who use it as a community center see it as such, but people who have more money and want to go to a fancy dinner with a visiting author have that available to them as well.”

In her community, people who can’t financially support the library do so in other ways.

“At my library we occasionally need someone to garden or fix the chimney, things like that,” she says. “People have interesting skillsets that the library might otherwise need to pay for, and we reach out to them.”

We must create frameworks for communities to be more deeply connected to each other using the station as a hub or platform.

In Nashville, Tenn., reporter Emily Siner routinely interviews people doing interesting things in the community in front of a live audience. The event series is later turned into a podcast and a newsletter — ensuring that a feedback loop is created between the station and Nashville Public Radio’s audience in person, then on digital, and then through email.

“Nashville is booming — people are moving to the area in droves, and many of them are young professionals who love NPR and This American Life and Serial,” Emily told me in an interview later published on Poynter.com. “But after meeting a lot of people like this, I noticed that very few of them seemed to feel a connection specifically to Nashville Public Radio. And it makes sense: There aren’t opportunities to see the station firsthand if you’re not a pledge drive volunteer or a big donor; we have great local news but no local show or podcast; and young people tend to be more transient and therefore less rooted in a community.”

The events Emily runs are free, but require an RSVP online — with an email address — which the station can later use to connect with participants who attend.

“Creating a live event that could double as a podcast seemed like the best of all worlds,” says Emily. “After all, the whole point of digital initiatives is to connect with your audiences better. What better way to connect with your audience than to bring them into the physical world with you?”

The events also help connect community members with each other, using the public radio station as a platform for doing so. Providing a way for people to meet and more deeply connect with each other helps create connections that can strengthen the community with and through the public radio station.

And it drives people into a deeper relationship with the station: they are not only aware of the station, but have an experience within it, which fits neatly into an engagement strategy that could later turn those people into loyal advocates on behalf of the station.

Some stations have robust events programs, but seeing those events programs or the engagement strategies I outline above as key can help strengthen the core functionality of a station while inviting the community to connect with each other at the same time.

We must incentivize stations to collaborate and share content and/or code.

Stations would save thousands of dollars a year if they could share code and story ideas or work together on collaborative projects. For example, stations could:

Collaborations can create better journalism, make it easier for stations to adapt as technologies change, save money, and help serve communities in a more robust way.62

However, there are challenges that prevent content, code, and strategy collaborations from taking place on a mass scale. Stations currently compete for existing financial resources. Words I heard when I suggested these ideas to membership departments include “poaching,” “competition,” and “stealing our potential leads.” Many stations see other stations as competition: they’re competing for pledge dollars, for foundation and grant dollars, and for listeners on-air.

But listeners don’t always affiliate themselves with a single station and this is likely to grow more true as mobile and on-demand platforms increase usage. People I interviewed said they wanted to donate to a specific podcast, or that they still listened to the station from the place where they grew up or where they went to college — or wished they could. They want ways to affiliate with and find material from more than one station. Newsletters and programming could help with this, but there are currently more deterrents than known benefits for doing so, and no one wants to be put at a disadvantage by sharing if no one else decides to share.

This would require different incentivizing strategies, both at stations and at grant-making institutions. Frameworks and processes need to be designed that reward helping and collaborating within the system and not keeping data, information, or software close to the vest. (For example, several people brought up the YMCA in this discussion. YMCA branches allow YMCA members from any branch to use their facilities. Are there some benefits that could be extended to members of any public media station?)

We must develop different communications strategies for stations to contact remote contributors or donors.

A number of people told me that they contribute to stations or station podcasts outside of their geographic region and receive mail or phone calls directed at more local listeners. For example:

“I get random bulk direct mail from WNYC because I donated to a podcast — they ought to be able to see that I don’t live in their listening area (they have my address) and that I gave via a podcast and tailor their outreach to me around podcasting.”

Donors or listeners outside of a certain geographic radius should receive customized e-newsletters and messaging. In fact, this could provide stations with an opportunity to target expats or people who no longer live in their geographic area. This could also be a way to introduce people to the public radio station in their new geographic area.

We must develop more ways to facilitate both creation and distribution of information.

Much of this report discusses ways that the public can become more involved and invested in public media. There are already a number of projects in existence — both inside and outside public media — that are audience-centered; that is, by including the audience in the reporting process, they make the audience more invested in the story or outcome. Many of these projects were detailed earlier in this report, but there are also initiatives outside of storytelling that facilitate deeper connections within a community. Many of these would require grants and/or additional resources or partnerships. Some ideas:

We must think about the legal and technical frameworks that could facilitate a more collaborative model.

Stations need tools and platforms that let people collaborate. And public media as a system needs to determine what legal frameworks would be put in place for work done in collaboration with the audience.

For some projects, existing licenses like MIT/GPL for software and Creative Commons for content could be used. For others, public media might have to create standard, easy, and reliable licenses.63

Licensing content with a creative commons license would allow public media content to travel more widely and reach new audiences. And openly publishing computer code would save stations money by producing a more secure, reusable product.

It would also help stations collaborate more easily with each other and with the public. As Eric Newton wrote in his book Searchlights and Sunglasses, “If we unleashed open source software applications and the technology needed to operate them and gave away money for code and machines to news organizations across the country, we would be building a new field of public media innovation — by repurposing existing content and creating new content.”

We must think about what it means to be a member.

Throughout this project, I have asked people working within public media to tell me what it meant to be a member of a public radio station. Several people told me that they had trouble coming up with an answer. “It’s code for a donation,” said a few people. Another person asked me if I was talking about tactile things, like tote bags. No, I said — not stuff. Then she said, “As a higher-type relationship, I’m not sure we articulate that very well.”

We must be able to tell the story of what public media is and why it matters, and to explain why people should support it — whether through financial means, time, story ideas, or other types of involvement. And non-financial forms of involvement should be valued as much as financial ones, particularly if they’re viewed as opportunities that could lead to further or deeper engagement with a station.

Between May 8 and June 15, I surveyed 225 people through a Google form, asking them to reflect on their membership (or lack of membership) at their local public station. Eighty-five percent of the respondents were under 60 and 49 percent of respondents were between the ages of 25 and 35. Thirty-eight percent of respondents were members of their local public radio station and half said they listened to public radio quite a bit — at least a 7 on a scale of 1 to 10. Among the people who said they listened a lot but were not members, reasons for non-membership were characterized by the following themes:

I don’t know what I would get out of membership:

I honestly don’t know what it is/what benefits I’d get from being a member. I listen mostly to NPR through podcasts.

If membership had usefulness to me, I might think of it as a service for purchase.

Not sure about the benefits. Also not sure where my money goes. It’s hard to spend money if you don’t know that it’s being effectively used.

Don’t really think of membership as a “thing,” just something that gets talked about when asking for money

I had no idea one could be a public radio member and have no idea what membership means.

I listen online or exclusively to podcasts and not a station on the radio:

I listen to podcasts more than radio these days (and mostly non-public-radio podcasts).

I transitioned a couple years ago to consuming primarily podcasts (and music), and not listening to over-the-air radio at all. I do contribute to podcasts, some of which are associated with public radio, however.

I used to be, but I’ve switched to podcasts and free streaming radio because the calls for donations were irritating and I like the ability to customize my listening. I can’t afford to give much.

Define Local. Define Radio. Define member. I have given a paltry donation to The Memory Palace podcast. I have also participated in New Tech City’s Beyond Boredom (is that what it was called?) project…so I did donate with my time and with my digital information, so that counts as something, eh?

I’m honestly just thinking about the value it provides to me since I hardly ever listen to it. I listen to NPR stories, but online, with no connection to my local station.

I listen to audio strictly via downloaded podcast or streaming. If I choose to donate to a show, I’ll do it directly.

I listen to public radio through podcasts associated with a lot of different stations. I support by doing random one-time donations to particular shows or stations at random times (Radiotopia, etc.). I don’t have the same kind of identification with, say, WAMU, that I may have if I had a long driving commute and really got to know the particular station.

I could never decide what station to commit my membership to — I listen to podcasts, NPR One, and PRI/PRX/APM content directly much more often than I turn on the local FM station that actually asks for my pledge. I’ve lived here 2 years and still don’t know the call letters.

I don’t have the money to give to a station:

Not a ton of disposable income.

I don’t have the expendable income.

Lack of disposable income.

No disposable income.

I am not a member of a public radio station because I don’t quite make enough yet to feel comfortable giving to a station. One day I hope to.

Each of these responses represents a person who is not able or willing to donate financially but who may be willing to become engaged in other ways that are valuable to stations. As more and more listening takes place off-air and on demand, stations will need to clearly articulate why they matter and how they serve their communities. By broadening the ways community members can become members — and become involved in the station itself — stations will create networks of people who can articulate why their local station is a valuable community resource.

We must work in public.

What differentiates public media from commercial media? In their 2009 paper Public Media 2.0, Jessica Clark and Pat Aufderheide wrote: “Commercial platforms do not have the same incentives to preserve historically relevant content that public media outlets do. Building dynamic, engaged publics will not be a top agenda item for any business. Neither will tomorrow’s commercial media business models have any incentive to remedy social inequality.”

Public media is not or should not be in competition with for-profit media. As Bill Siemering wrote in NPR’s original mission statement, “National Public Radio will not regard its audience as a ‘market’ or in terms of its disposable income, but as curious, complex individuals who are looking for some understanding, meaning and joy in the human experience.”

Public media strengthens itself by working in public and with the public: by sharing ideas, content, and platforms, public media can bring more people into the fold to support and create material for the public. Working in public strengthens the journalism public media produces and the institution of public media itself. If stations can share how they work and what they’re on working on with a wider audience — through a mailing list or through social media — audiences will become invested not only in the process, but also in the final product.64

Working in public also teaches people who don’t work in public media how to create and distribute content. This will help continue public media’s work “to reach and engage with audiences, when and where they choose, with content important to their lives.”

Above all, we must think about and learn from the user, the audience, the listener, the person, and the public.

All of these ideas come back to the listener, the audience, and the public. How do we best serve the public?

Recently I tweeted that I was planning to move to Chapel Hill and asked if the local public radio station had any suggestions for radio pieces to listen to before I arrived. They did — and created this website.

The website is designed for newcomers to Chapel Hill — people who might not have their media habits set in stone. It’s designed for the public and, in this case, with the public’s help. It was not something that existed before I reached out.

When stations get ideas from the public in this way, they strengthen their ability to serve the individual and celebrate the human experience.65 Partnering with the public will help public media feel irreplaceable, regardless of whether it airs on the radio, or on TV, or through an app, or on demand. It will help the public understand the importance of public media — and help public media understand the importance of the public.

I would like to thank the Knight Nieman Visiting Fellowship program, especially Ann Marie Lipinski and Joshua Benton, for their guidance and support throughout this project.

Thank you to everyone across the public media landscape who spoke to me, shared ideas, or pointed me in directions I hadn’t anticipated. A particular thanks to Bill Siemering, Barry Nelson, and Mark Fuerst for supplying me with a lot of background material.

To all of those who have championed this in ways big and small since last August: I’m excited for the next steps, which will focus on building out software platforms to make it easier for stations to connect with audiences and each other.

And to A and Sadie — who edited all of this and provided lots of love.

Melody Kramer is a 2015 Knight Visiting Nieman Fellow and is currently serving a two-year term appointment with 18F. She was previously a digital strategist and editor at NPR. Based on her research, she is launching Media Public; sign up here for more information.

]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

]In my role as Project Coordinator, I think I have fostered community by:

- Being authentic in my engagement (using my voice not hiding behind the Smithsonian, and being enthusiastic because this stuff is pretty cool),

- Asking questions that furthered the dialogue (how did you hear about us? what did you think of that? what was most surprising? what would you like to do next?)

- Establishing a rhetorical approach that made it clear that we/I was learning at the same time as the volunteers

- Establishing a rhetorical approach that suggests there is ALWAYS more to the story and that this is a chance to make discoveries — and then by recognizing or acknowledging those discoveries

- Creating the hashtag #volunpeers to allow volunteers to leverage the structure of social media spaces to communicate with one another and with me/us — encouraging them to use it as well to ask for help or indicate a project needs review, etc

- Creating collaborative competitions, rather than leaderboarding: #7DayRevChall (7 Day review challenges) allowed people to contribute collectively to a goal, then metric and try to beat the group goal — and using daily updates to share progress. This also allows for skills acquisition and learning best practice for review AND addresses an issue we see frequently — folks love transcribing and pages languish waiting for review. Every 2 months, we draw attention to this

- Focusing on the process of transcribing and reviewing often over the volume of the product — and cultivating/encouraging patience from experienced volunteers in regard to “newbies”

- Letting volunteers speak to each other directly in spaces in which they already live and are comfortable (Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.) We have benefitted from volunteers who are welcoming and want to help each other complete projects

- Also by engaging through those 3 social media networks (also instagram some and hopefully reddit soon), volunteers have the ability to “curate” and own their experience and the product they have created. My perception is that creates more in-depth brand engagement, as well — these volunteers listed “digital volunteer for @TranscribeSI” or “#volunpeer for @TranscribeSI” in their social media bios

- Listening to the feedback and description of external interests from volunteers and gauging their excitement in subject matter — then actively courting the archives, museums, and libraries that have related material

- Finally, actually integrating their feedback into site design, when it’s possible to do so.”

]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

] ]

]